Some minor spoilers below.

Some minor spoilers below.

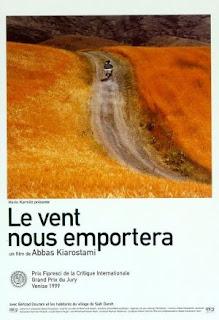

Of Kiarostami’s films that I have seen so far, The Wind Will Carry Us is easily the most elusive and mysterious. An Engineer arrives in a small town with a small crew, and the only information given about their journey to this area is that they are anticipating the death of a hundred year-old woman and the subsequent ceremony. The Engineer receives phone calls from a woman who naggingly checks up on the status of the project a few time a day, and he befriends a boy who, much to the pleasure of Kiarostami, considers his studies to be the most important part of his life. As the days wear on, the old woman shows signs of improvements, and from here the tension in the film mounts. The phone calls, which require the Engineer to drive up to the top of a hill for better reception, become more frequent, an earthquake buries a man alive, and the young boy refuses to speak to the Engineer he scolded him for giving out information to someone who he shouldn’t have. The film will end with many of these plot points unresolved.

Much of this film is about the ‘between’ step, the limbo of a process. When the Engineer receives a phone call, every time, it is put on hold while he runs to his car, and then drives up a typically winding path where he can resume the conversation, out of breath. A man digs a trench at the top of this hill, the job handicapped and stalled after the tremor. The Engineer befriends a woman across from the balcony of his lodging who is pregnant with her 10th baby, living in the disabling trek between conception and labor. And then there is the viewer’s relationships with these people, rarely fully developed if only because we never see them or know their names. I believe the only character who is given a name and a face is Farzad, the boy studying for his exams. This distinction creates a crux of his character, one that directly contrasts the films other crux, the dying invalid. Farzad is thriving and growing and learning while the invalid, and the visiting crew, awaits her death. The Engineer, the film’s protagonist, dwells between these two poles of life. Farzad finds a domain in the school and the invalid a domain in her deathbed, but the Engineer runs from place-to-place, racing back and forth from the hilltop, fetching milk, and scampering away from his tea time, absentmindedly leaving behind his camera, at the slightest distraction.

The bone in the end drifts, zigzagged again, down the stream, between the top and the bottom. It is one of the most overt symbols of mortality, a bone without flesh. While the bone may still exist, it is a reminder that the mind of the person who used to rely on this leg bone for walking doesn’t; the mind that has escaped the limbo that is life, the stopgap between oblivion and oblivion. Up until this film, I’d have described every film by Kiarostami that I’d seen, save for his early The Traveler, as the simplest and purest representations of love, not the weepy swoony kind that occurs between two lovers, but the essential love and respect that occurs being two beings, regardless of how they feel toward each, or how well they know each other. The Wind Will Carry Us falls in this category. It’s there amongst the Engineer and Farzad, and it’s between the Engineer and the invalid.