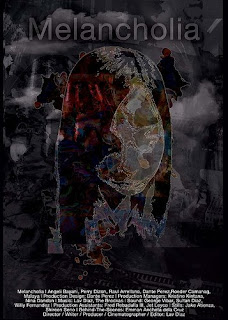

The length of Melancholia is the default point of interest when I describe the film to people. It is also one of the least important aspects of the film. Running somewhere between seven and a half to eight hours long, it is still only Diaz’s fourth longest film. An amazing thing, though, is that it actually needs to be this long (Okay, it could probably lose an hour and still retain everything that is so magical about it, but the point is there). Diaz often cites his frustration with journalists and press who, when given a rare opportunity to discuss the film with him, only bring up the length, and even worse, to ask ‘why so long?’ His response? ‘Next please.’

The length of Melancholia is the default point of interest when I describe the film to people. It is also one of the least important aspects of the film. Running somewhere between seven and a half to eight hours long, it is still only Diaz’s fourth longest film. An amazing thing, though, is that it actually needs to be this long (Okay, it could probably lose an hour and still retain everything that is so magical about it, but the point is there). Diaz often cites his frustration with journalists and press who, when given a rare opportunity to discuss the film with him, only bring up the length, and even worse, to ask ‘why so long?’ His response? ‘Next please.’

The easy summation for the film is that it is about all of the sadness in the world, how every person has so much sorrow and melancholia, and we all have our ways of cloaking this sadness, even though it is always there. But this is to ignore all of the beautiful allegories of art, personas, interpersonal connection, and transformation that are just as prevalent, if not more so. The film is unofficially divided into three distinct ‘chapters’: The first is the Sagada segment in which Alberta is the protagonist, the middle segment primarily focuses on Julian after Sagada (Alberta is important here, too), while the final few hours follows three men through a jungle, all three on the brink of insanity and death. Despite the fact that Diaz has shot the entire film on HD video, the lengths of the shots felt like they were equal to the length of an entire film reel (much like Benning’s lake and sky films). In reality, they were probably a bit longer, probably averaging 13-15 minutes per shot, I would guess. Also, most of these shots are static and fairly distanced from the characters; I don’t think Diaz ever allows a close, clear look at any character’s face. By never distinctly revealing the physical identity of the characters, it keeps them in a constant state of development limbo; there is always something unknown about them.

Speaking of limbo, one of the film’s big ideas relates to purgatory (Diaz even released a short film in the last year or so titled Purgatorio). Characters are caught between locales, personas, and states of mind, and they all realize it. Faced with their sorrow, Julian, Alberta, and Rina all make a sort of pact with each other to assume the roles of completely different people. When we first meet them, Alberta is a prostitute named Jenine, Julian is a pimp named Danny Boy, and Rina is a nun roaming the roads of Sagada begging for ‘charity for the poor.’ The illusion of these characters’ false personas is breached when a man recognizes Alberta and confronts her at a restaurant. She assures him that she is not Alberta, he swears that she looks just like her except for her clothing, but he seems to take her word that she is just a whore named Jenine. Later, when the same man asks ‘Jenine’ for her services, he stops her mid-way through her stripping, finally convinced that she couldn’t be Alberta, because Alberta would never strip like this for a stranger. Of course, though, it is Alberta. That he has become so convinced by this gesture gives an idea of the complete unlikelihood of these roles changes, and the commitment beyond all of their morals that they have agreed to. It’s the ultimate example of method acting.

Post- ‘persona adoption’, the middle segment of the film finds the characters in a deeper ‘purgatory’ than before. Julian seems to be employing performance artists to stage didactic and absurd performances in his living room, as well as a thrash jazz/metal band, who wail on their instruments for a good twenty minutes as Julian wanders around them, grinning and sipping a beer (this part lost the largest chunk of my audience, though it takes place five hours into the film). Alberta, returning to her day job as a school principal (but is it her real day job?…), puts her emotional sterility on hiatus to conduct a new search for a missing loved one, this time for her adopted daughter Hannah, who has, coincidentally, begun pursuing prostitution to ease her troubles over her dead parents. Diaz uses this segment to express his passionate views on various aspects of filmmaking. Julian has a wonderful, extended visit with a writer friend to discuss his new book, ‘The True History of Filipino Cinema’ (I think this is what it was titled; if not, it’s close). Julian asks the friend to tell him a synopsis of the film, and, seemingly representing Lav Diaz himself, the friend becomes irritated that he should have to shrink the content of his work into an abridged form. “Just read the book!” he says. He gives in, though, for the sake of communicating more anecdotes on the problems with Filipino cinema, such as their reliance on big stars, tidy lengths, and heteronormativity.

Julian and Alberta meet in a cafe shortly after this scene, because Julian wants to discuss his irritation with her that she compromised truth and the illusions of their personas in the first segment when she addressed ‘Danny Boy the pimp’ as Julian. This was an intense dissection of what truth actually is when you are acting as someone else. How long do you have to ‘pretend’ to be a whore, actually having sex with strangers, telling people your name is Jenine, before they become your actual identity? We gives ourselves these names, and we dictate our moral boundaries, so why should Alberta the innocent widow still be Alberta the innocent widow? If we completely change our environment, names, morals, troubles and worries, and sources of happiness, then shouldn’t we cease to be who we once were? Beautiful stuff, this film offers.

Following the thrash/noise mind eraser (and exit music, for many), the music abruptly shifts to a jungle, and stays there (this segment is very reminiscent of the second half of Tropical Malady). At first, the three men that the film is now following are unknowns. Eventually, though, we see one of the men writing a letter or poem, with his writing translated in voiceover. He is writing about Alberta, and, thus, his identity is revealed to be Renato, Alberta’s missing husband whose absence has caused her so much grief. This also shifts the time of the film, as our sense of where we are goes back to about ten years earlier than the rest of the film is set. The next two hours shows, in snail-paced detail, the mental and physical disintegration of the three men, who are being hunted by unseen militia. When these scenes shift to night, the images on the screen are impenetrable for well over half an hour, more difficult to dissect, even, than the night scenes from Birdsong. The duration of this time with these men is, frankly, exhausting; their insanity and hopelessness arguably contagious.

The film has a coda, which both summarizes much of the film’s ideas, and also blasts it into hyper-spiritual incomprehension. Alberta has shifted her hunt from Hannah to Julian, who has inexplicably gone missing. Civilians have been replaced by performance artists/meditators/yogis. Alberta encounters a man who tells her that sadness is the source of all art; he is an actor because he has sadness; sorrow is how poets write poetry, and filmmakers create cinema. Alberta finds Julian, who is now God, or at least thinks he is, and accredits himself (God) as the source of all sadness and suffering. He assumes the ideal persona for overcoming his melancholia, by becoming the one who gives it.

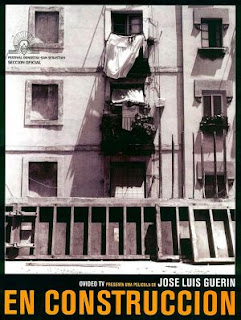

While this is, as usual for Guerín, a lovely experience unlike most in cinema, I had trouble with it in its role as documentation. Too real to be fiction, but too staged to be reality, there is a constant tension while watching this film that relates to how it was shot and how genuine it is, which distracts from the lyricism of the film’s conversations, philosophies, and imagery. It is quite an obvious comparison, I think, to call attention between this film and Zhang-ke’s recent 24 City. Both films’ subjects are modern high-rise residencies which are being built to replace a piece of each respective city’s history, and both films walk a tightrope between fiction and reality. Zhang-ke interviews about eight subjects, and roughly half of them are actors who are acting out scripted material for their interview, while the other half are genuine, unscripted interviews with actual civilians. En Construccion has a more subtle conflict with reality, in the sense that I believe that all of the film’s subjects are non-actors who are simply acting out their daily routines, similar to the characters in a Pedro Costa film. Certain moments, especially the young worker who flirts with a woman who hangs her clothes to dry, lose credibility for the entire film because they are so obviously set-up, including reverse-angle shots and cuts to accompany the already far-fetched possibilty that a confrontation this theatrical could be simply stumbled upon; it feels like an homage to Romeo and Juliet. Earlier scenes in which it seems like we are eavesdropping on the conversations of resident’s and passersby are reconsidered at this point. A dialogue between a little girl and her friend, discussing something like whether or not she wants to have children when she grows up, becomes slightly awkward in retrospect. Is this just an actual conversation that they were having at the site, or did Guerín script this, and if so, why? Did Guerín hear the conversation and ask them to repeat it for the film, and again, why? Not to mention that most of the dialogue that seems to be spontaneous sounds so well recorded that I wonder if these people were mic’ed, and if so, who got a mic and who didn’t? What other juicy material am I missing from those who weren’t mic’ed? Needless to say, the formalities of the film took center stage with me, and I can’t tell if it was intentional or not, nor if it benefited the viewing experience; my hunch is ‘no.’ A film like Close Up gets away with this blurring of reality because, among other things, it embraces the confusion and mixing of fiction and non-fiction.

While this is, as usual for Guerín, a lovely experience unlike most in cinema, I had trouble with it in its role as documentation. Too real to be fiction, but too staged to be reality, there is a constant tension while watching this film that relates to how it was shot and how genuine it is, which distracts from the lyricism of the film’s conversations, philosophies, and imagery. It is quite an obvious comparison, I think, to call attention between this film and Zhang-ke’s recent 24 City. Both films’ subjects are modern high-rise residencies which are being built to replace a piece of each respective city’s history, and both films walk a tightrope between fiction and reality. Zhang-ke interviews about eight subjects, and roughly half of them are actors who are acting out scripted material for their interview, while the other half are genuine, unscripted interviews with actual civilians. En Construccion has a more subtle conflict with reality, in the sense that I believe that all of the film’s subjects are non-actors who are simply acting out their daily routines, similar to the characters in a Pedro Costa film. Certain moments, especially the young worker who flirts with a woman who hangs her clothes to dry, lose credibility for the entire film because they are so obviously set-up, including reverse-angle shots and cuts to accompany the already far-fetched possibilty that a confrontation this theatrical could be simply stumbled upon; it feels like an homage to Romeo and Juliet. Earlier scenes in which it seems like we are eavesdropping on the conversations of resident’s and passersby are reconsidered at this point. A dialogue between a little girl and her friend, discussing something like whether or not she wants to have children when she grows up, becomes slightly awkward in retrospect. Is this just an actual conversation that they were having at the site, or did Guerín script this, and if so, why? Did Guerín hear the conversation and ask them to repeat it for the film, and again, why? Not to mention that most of the dialogue that seems to be spontaneous sounds so well recorded that I wonder if these people were mic’ed, and if so, who got a mic and who didn’t? What other juicy material am I missing from those who weren’t mic’ed? Needless to say, the formalities of the film took center stage with me, and I can’t tell if it was intentional or not, nor if it benefited the viewing experience; my hunch is ‘no.’ A film like Close Up gets away with this blurring of reality because, among other things, it embraces the confusion and mixing of fiction and non-fiction.