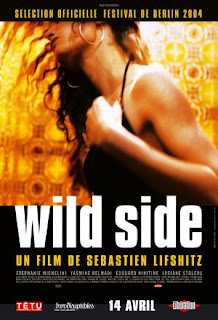

DVD: Wild Side (Lifshitz, 2004)

The lasting effect of Lifshitz’s most recent film (five years now and still nothing moving? sad.) is empty compared to the breezy and often lovely act of watching it. The cinematography is lush and the music calmly swells through its duration, but I was ultimately unsatisfied with the time that I spent with these characters. Into Wild Side (a shorter film than his more layered Almost Nothing), Liftshitz crams a great deal of nudity and sex which is consistently unconventional (no vanilla here) but hardly unheard of, and, sometimes, in latter scenes, boring. As liberal-minded as I like to think I am, I would have enjoyed the film much more if it had aimed to focus on what motivated the three main characters, Pierre, Mikhail, and Djamel, to participate and enjoy their polygamous relationship, especially considering Pierre’s transsexuality. Lifshitz might be expecting his audience to just go with the flow, which I did, and not ask questions, which I am. More frustrating is that the film might be making an attempt at developing Pierre, via shots of his childhood, dreamily photographed but only superficially nostalgic, focussing on his relationship with his sister, which was cut short, and getting bullied and beaten by other kids, which is the simplest and cheapest way of developing an un-straight character, and frankly not sufficient for a character who partakes in a lifestyle such as Pierre does.

The lasting effect of Lifshitz’s most recent film (five years now and still nothing moving? sad.) is empty compared to the breezy and often lovely act of watching it. The cinematography is lush and the music calmly swells through its duration, but I was ultimately unsatisfied with the time that I spent with these characters. Into Wild Side (a shorter film than his more layered Almost Nothing), Liftshitz crams a great deal of nudity and sex which is consistently unconventional (no vanilla here) but hardly unheard of, and, sometimes, in latter scenes, boring. As liberal-minded as I like to think I am, I would have enjoyed the film much more if it had aimed to focus on what motivated the three main characters, Pierre, Mikhail, and Djamel, to participate and enjoy their polygamous relationship, especially considering Pierre’s transsexuality. Lifshitz might be expecting his audience to just go with the flow, which I did, and not ask questions, which I am. More frustrating is that the film might be making an attempt at developing Pierre, via shots of his childhood, dreamily photographed but only superficially nostalgic, focussing on his relationship with his sister, which was cut short, and getting bullied and beaten by other kids, which is the simplest and cheapest way of developing an un-straight character, and frankly not sufficient for a character who partakes in a lifestyle such as Pierre does.

As unilluminating and unfortunately forgettable as the film is, it was still formally engaging, brilliantly acted, and, again, aesthetically lulling. The film zooms by, feeling much shorter than its ninety minute running time. A lot of the time spent watching it, especially in its former half, is devoted to identifying the characters and their relationships to one another, and to sensing Lifshitz’s timeline, which is more complex than the also non-sequential narrative of his Almost Nothing. Threads of the plot go unexplained and untied for much of the film, and many remain so. Lifshitz seeming fixated on making films that do not contain typical queer film stereotypes and lack of ambition. And he succeeds, even in relation to non-queer cinema, but I got the feeling here that he still uses the queer themes as a bit of a crutch, as if the unconventional sexuality is supposed to be engaging enough to sustain a story that might not be up to snuff, which isn’t the case with this film. Pierre is returning home to care for her sick mother (a motif for Lifshitz?), once again enforcing an air of doom for not just the mother, but for all characters that are affiliated with her. A tranny caring for her dying mother, the groundwork for a great film. A prostitute tranny, involved in a relationship with two men with ambiguous sexualities, caring for her dying mother; even better. But the film too often aims to entice with inconsequential nudity and bareback sex with strangers, instead of addressing its strong premise. Even Antony’s brilliant ‘I Fell in Love with a Dead Boy,’ performed as a kind of prologue, is narrowed by this pedestrian study of sexuality, as the song seems to only exist in the film for its “are you a boy or a girl?” coda, ignoring the delicacy of the rest of its verses.

DVD: Wild Side (Lifshitz, 2004) Read More »