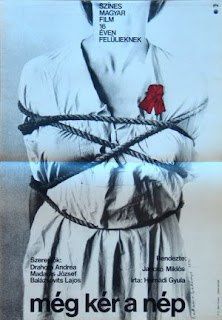

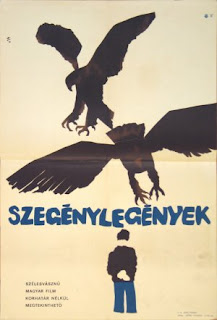

Cinematheque: The Red and The White (Jancsó, 1967)

In one corner, this could be the most realistic war film ever made; not only realistic in the sense that it can often pass as actual, filmed documentation of battles and wartime, but also that it is showing the situation objectively, and from enough of a distance that all hints of the filmmaker’s intentions remain ambiguous even after it is over. Typical of Mr. Jancsó, the film is shot in very long, elaborately choreographed shots in which the camera circles and maneuvers its way in and around the characters and the action. This can beautify the war in some sections, but leave it stern and brutal in others, depending on how intrusive the camera actually is. At times, the camera, fairly close up, is transitioning from object to object, person to person, so seamlessly and well-choreographed, that it feels too rehearsed, or even too logical. These rare but well-dispersed sequences are the lone circumstance in which Jancsó takes control of the action and his audience, and guides the viewer through precisely what he wants us to see. The camera is usually backed away enough to decide for oneself what, in this busy and chaotic assemblage of violence and backstabbing, to focus on, not dissimilar to the tension and freedom granted from a deep focus conversation.

In one corner, this could be the most realistic war film ever made; not only realistic in the sense that it can often pass as actual, filmed documentation of battles and wartime, but also that it is showing the situation objectively, and from enough of a distance that all hints of the filmmaker’s intentions remain ambiguous even after it is over. Typical of Mr. Jancsó, the film is shot in very long, elaborately choreographed shots in which the camera circles and maneuvers its way in and around the characters and the action. This can beautify the war in some sections, but leave it stern and brutal in others, depending on how intrusive the camera actually is. At times, the camera, fairly close up, is transitioning from object to object, person to person, so seamlessly and well-choreographed, that it feels too rehearsed, or even too logical. These rare but well-dispersed sequences are the lone circumstance in which Jancsó takes control of the action and his audience, and guides the viewer through precisely what he wants us to see. The camera is usually backed away enough to decide for oneself what, in this busy and chaotic assemblage of violence and backstabbing, to focus on, not dissimilar to the tension and freedom granted from a deep focus conversation.

Regarding the viewer’s attempts of ‘siding’ with someone in the film, there isn’t really a protagonist in which to sympathize; one is able to sympathize with whichever side of the conflict he chooses, and pickin’s are slim, as the title of the film spoils: you have your Communist Reds or your Tsarist Whites. I couldn’t care either way, which brings me to the other corner of the film’s realism: why depict an historical event, that actually happened, and present it as it is here, in glorified realism? Where does that leave the viewer who has no association with the film’s politics? Since the film is based on events that took place just before the 1920s, it is in the realm of possibility that the events here could have been filmed, documented in motion pictures; this is a trait that his The Round-Up does not have since it was set in the early 19th century, before film or any other means of moving pictures were developed. Round-Up entertained the audience’s potential lack of an entry to the material by incorporating a humanist plot to which anyone could relate. Here, though, it comes across as purely a showcase for Jancsó’s skill at directing excessively garnished action sequences; an empty-headed blockbuster. A drawn-out, recreated battle between Reds and Whites is just as banal and pedestrian as your everyday battle of good vs. evil, and is not enough to make this a worthwhile exploration of an important historical event.

Cinematheque: The Red and The White (Jancsó, 1967) Read More »