“For Flaherty, what is important about Nanook hunting a seal is his relationship with the animal, the real extent of his wait. The length of the hunt is the very substance of the image, its true subject. In the film, this episode is thus composed in only one shot. Can anyone deny that it is much more moving as a result than montage of attractions would have been?”1

– André Bazin

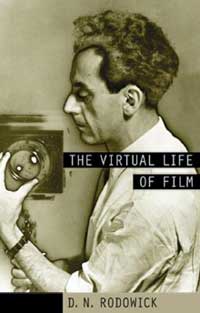

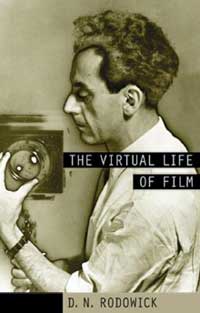

As cinema continues to finalize its transition from a medium composed of celluloid grain into one composed of digital pixels, it is important to take a closer look at some differences between these two means of producing a moving image. As D.N. Rodowick notes in a chronological outline of this transition, cinema has been under the influence of digital technology since digital image processing and synthesis was introduced in the 1980s2, though this development merely allowed for special effects work to be done on films shot on celluloid. The real game-changing shift comes not only with post-production digital editing advancements, but also with the advent and ubiquity of digital capturing devices. ‘Films’ are being shot on hour-long digital tapes or with cameras rigged up to hard drives rather than 11-minute-capacity reels housing a thousand feet of celluloid. But for digital filmmaking to take possession of its “area of competence,” as Greenberg would say, it must determine and utilize that which is exclusive to itself as a medium.3 Of all that is unique to this new medium of cinema, I cannot see a more significant trait than its drastically extended allowance in shot length.

Additionally, if one wishes to look at just how varied our perception of the cinematic image is by this development, one would find a strong model in the genre of ‘structural’ filmmaking. P. Adams Sitney, who first named and outlined the characteristics of the genre, defines this avant-garde niche as one “wherein the shape of the whole film is predetermined and simplified, and it is that shape that is the primal impression of the film.”4 With a film that is about shape, and the deconstruction and minimizing of that shape, the work acts as an exposé of the formal paradigms that construct the narrative cinema. Michael Snow’s canonical structural film Wavelength is practically the example of this commentary. In “Toward Snow,” Annette Michelson’s seminal piece on Wavelength, she outlines the film’s deconstruction of narrative form. She writes, “The film is the projection of a grand reduction; its ‘plot’ is the tracing of spatiotemporal données, its ‘action’ the movement of the camera as the movement of consciousness.”5 She then adds, “Voiding the film of the metaphoric proclivity of montage, Snow created a grand metaphor for narrative form.” Given that he has taken on digital recording methods with some of his recent moving image work, there is not a more appropriate artist than Michael Snow to look at the shifts in perception that have been born from digital filmmaking’s extended long takes.

Snow’s 2002 video piece Solar Breath (Northern Caryatids) is a worthy candidate for this examination, both for its formal make-up (it is a single, static shot that lasts for 62 minutes), and for its primary subject (a pair of windows), which has a striking resemblance to the aesthetics of Wavelength. Throughout Solar Breath’s running time, the drapes hanging on the viewer’s side of the windows dangle, whip, and react to the wind that flows in and out of the space through one of the windows that has been left open. Though this window is open, there is still a screen that stops the drape from exiting the space. The drape, therefore, smacks lazily against the screen as the wind attempts to suck the undulating fabric out of our space and into the outdoors. On a small number of occasions, the drape will blow forward far enough to give the viewer a glimpse of the outside, where a solar panel sits on a table in the lawn, soaking in the sun, generating the energy that is potentially allowing the video camera to operate and record that which we are seeing. While all of this takes place – seemingly in real time without any breaks in the action – non-diegetic sound of someone eating fills the soundtrack.

That Solar Breath is a single shot of a set of windows steers it directly into dialogue with Wavelength (never mind that they were both made by Michael Snow). While Solar Breath genuinely has the appearance of being a single shot, Wavelength is very much a different story. In his original statement written for the release of the film, Snow purports Wavelength to be “a continuous zoom which takes 45 minutes to go from its widest field to its smallest and final field,”6 even though the material nature of celluloid, as well as the jumpy visual appearance, reveals this to not be the case. Michelson skimps around this claim, hazily mentioning the disruptions in the zoom in her description of it, saying that it is “by no means absolutely steady, but proceeding in a slight visible stammer.”(“Toward Snow,” 174) Shot with various stocks of 16mm film – some expired, some current – the film is very much a collection of reels. Not that it is any big secret that Wavelength was not actually done in a single take (the film goes from day to night and back to day in the course of 45 minutes). The reality of the matter is that Wavelength, a film made in 1967, couldn’t have been done in a single, 45-minute take even if Snow had wanted to; no reels of film, neither in 1967 nor now, support shots that are even half that length. The illusion that what we are seeing is continuous is an intuitive connection between our awareness of the limitations of the medium, and our detection of the intentions of the filmmaker to overcome these limitations.

Pier Paolo Pasolini, who coincidentally published his article “Observations on the Long Take” in the same year of Wavelength’s premiere, likens the long take to that of our own present perception:

“Reality seen and heard as it happens is always in the present tense. The long take, the schematic and primordial element of cinema, is thus in the present tense. Cinema therefore ‘reproduces the present’.”7

If the lingering shot is the present of a particular, subjective observer, it remains a reproduction of the present until it is finished, whereby it becomes the past, allowing for interpretation. Pasolini’s theory develops to posit that a shot’s meaning can only be given value once it is finished; like with human life, the possibilities of relations and meanings and developments is endless, “chaotic,” until it is over. This reveals Wavelength to be an anomaly of sorts. When its shots end, they are each followed by a brand new shot that begins in almost exactly the same place, with almost exactly the same perspective of exactly the same room as when the previous shot ended. While Pasolini sees montage as the construction of an objective viewpoint – the selection of the best of every possible subjective perspective to present objectivity devoid of the present – Wavelength exists as a montage that retains its subjectivity and its illusion of the present.

Bazin’s opinion on long takes differs from Pasolini’s in that it promotes long takes in order to retain the objectivity, rather than the subjectivity, ingrained in the single, unedited shot. He speaks of three different types of editing, and “All three have a common feature, which is the very definition of editing and montage: they create meaning which is not objectively contained in the images and which derives solely from placing these images in relation to one another.”(“Evolution of Film Language,” 88-89) In Bazin’s essay “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,”8 he details how a photograph, captured on emulsion, presents the photographed subject in the present. The photo is objective proof of the subject’s existence. Similarly, a motion picture film presents the change of the subject objectively. This change in the subjects exists as it was captured, regardless of image distortion. The objectivity of this change is interrupted, though, with montage, which introduces the subjectivity of the editor, inviting interpretation and meaning that was not invoked in the original shot. Going back to Bazin’s thoughts on Nanook’s hunt, the duration of his wait is presented in its actual temporal form; the wait that we experience in watching the hunt is identical to the duration that Nanook experienced at the original moment of filming. It is, thus, made present again in the viewer. Any cuts or edits in this shot would extinguish its validity as an objective document of the duration of Nanook’s wait.

There are comparable problems with this theory, again, when it is matched up with Wavelength. Because the shape of the structural film is the subject of the work, it is the zoom that should be considered the subject of Snow’s film (as opposed to the walls of the loft, any of the human performers, or the photograph of the waves). Going by Bazin’s ideas, then, the film is a document of the change of the zoom, and the duration of that change. The duration of the camera zoom at the heart of the film is fixed at 45 minutes once the starting point (the back of the loft), end point (the photograph), and the zoom speed are determined, all of which is set in the first moments of the first reel. The camera’s projected zoom is intermittently broken up by cuts, but, again, each shot progresses in the same direction at the same speed. Repeating one of Michelson’s key thoughts, “[Wavelength’s] ‘action’ is the movement of the camera as the movement of consciousness,”(“Toward Snow,” 175) the film presents only one consciousness. The fact that the zoom is broken up into many parts is inconsequential to the duration because all of the shots are intra-subjective, giving the illusion of a continuous trek. Wavelength successfully functions as a document of the duration of a 45-minute zoom through a loft because of this approximate continuity among its successive shots. The objective duration of the zoom would be the same as one shot as it is as several.

That Wavelength represents a single journey despite being composed of several shots is a result of the viewer’s intuition of the mode (celluloid) in which it was captured. This is a cognitively formulated suspension of disbelief, but as Rodowick details, it is also an inevitable awareness that is inherent in, and shapes the way that we perceive, every creative medium:

“A medium, then, is nothing more nor less than a set of potentialities from which creative acts may unfold. These potentialities, the powers of the medium as it were, are conditioned by multiple elements or components that can be material, instrumental, and/or formal. Moreover, these elements may vary, individually and in combination with one another, such that a medium may be defined without a presumption that any integral identity or an essence unites these elements into a whole or resolves them into a unique substance.”9

Thus, in McLuhan-ist fashion, the potential of the recording medium is a very important factor in its interpretation, in large part because we know what something can and cannot do, and therefore are more open to compensations. This is why the emergence of a medium such as video provokes new grounds for the perception of the extended long take. With video, several-hours-long shots are possible.

A sample of some of the structural filmmakers who have taken the plunge into digital capturing methods, other than Michael Snow, includes Ernie Gehr, Jonas Mekas, and, most recently, James Benning with his 2009 film Ruhr. Benning makes for an interesting model at this point, because a majority of his films are founded on durational concerns that he explores in long, static shots. Ruhr is Benning’s first ‘film’ not captured or exhibited on celluloid in thirty-two years of filmmaking, and contains the longest shot of his career, coming in at 60 minutes. Mark Peranson described this shot in his review of the film in the Winter 2010 issue of Cinema Scope magazine10:

“Relieved of the necessity of changing camera rolls, Benning goes all out with a mesmerizing shot of a coke-processing tower in Schwelgern, where every ten minutes water pours down onto the base and creates a billowing pillar of steam leaking through the steel-latticed structure and into the atmosphere; the tower looks that it is on fire. As it repeats, surrounded by clouds it itself creates, the image takes on a psychedelic quality, with each billowing blossoming into differing colours, a function of both the material being processed as well as the changing quality of light.”

As a continuous documentation of the repeating cycles of the steam from the tower, and of the daylight’s shift into the darker tones of the evening, this kind of shot is unique to the technology of video capturing. No form of celluloid could present the entire duration of this event.

A peculiar anecdote in the same review reveals another facet of video, and at the same time calls into question its indexicality. Near the end of his description of Ruhr’s concluding shot, Peranson reports, “the shot grew dark faster than time allows – Benning condensed 90 minutes to 60, in effect speeding up the sunset”(“Ruhr,” 57) (*Note – According to an interview with Benning, the shot was actually narrowed down to 60 minutes from a 120- minute shot11). In this off-hand factoid, the credibility of the documentary value of the shot virtually vanishes. The shot, which is perceived to be a particular duration in the film, is revealed to have been twice as long in the original captured moment. First of all, it is important to note that there are two methods in which Benning could have eliminated that hour of running time. Either he sped up the video to play at 200% its captured speed, or he cut out a chunk from somewhere in the middle, and joined the remaining fragments through very slow dissolves and color correction. In the aforementioned interview with Benning, he reveals the latter method to have indeed been the case, but it is the potentiality of both options that questions and complicates the ways that we perceive video and its indexical value for duration and change.

To capture, and then playback, a document of a subject’s change in a manner which can be deemed to be indexical, there is a responsibility placed on the coordination of frame rates in the production and post-production development of the shot. In the analogical medium of celluloid, options for deviating from this coordination have always been slim, and have only gotten more strictly defined since the end of the silent era. Presently, 16mm and 35mm films are almost universally shot at 24 frames per second; with super 8mm, one has the added option of 18 frames per second, and the silent era saw a range of complicated frames rates, some of which, such as 17 frames per second, are awkward prime numbers that are practically incompatible with any of today’s projectors. While many of these frame rates were used for slow motion or fast motion techniques, the options for projecting a film at a frame rate that is different from that which it was captured, while still retaining an illusion of being ‘real-life’ speed, are nil (anything less than a 10% speed change will be imperceptible to most eyes). Even so, a film projected at a faster or slower frame rate than which it was shot is still, materially, unaltered.

Video, on the other hand, has a wide and complicated array of potential digital speed alterations. In editing suites such as Avid and Final Cut Pro, video can be sped up or slowed down by as little as .01%. Changes in video speeds will result in one of two distortions in the frame counts: in progressive video, frames will intermittently be dropped so that the final running time corresponds to the calculated manipulation, and in interlaced video, two frames will weave themselves together in order to compensate for the lost or gained time. In Europe, where the PAL video standard calls for frame rates of 25 frames per second instead of 24, films are telecined with a 4% speed-up to compensate for the difference, yielding very slight, though imperceptible fast-forward in practically every video available in the continent. The reality of this type of speed-up, though, originates in the post-production process: a film shot on either celluloid or video is subject to this manner of durational manipulation.

In contrast, the potentiality of the technique of ‘seamless splicing’ (i.e. Benning’s method of halving the duration of his shot of the coke tower) is rooted in the moment of capture. In the Fall 2009 issue of Cinema Scope12, Benning recalls the circumstances for another shot used in Ruhr in which seamless splicing was also used:

“I began filming…in a wooded area adjacent to the Düsseldorf International Airport. There was no wind. It was absolutely still, not one leaf was moving. The high definition captured every tiny twig…I found the frame and pushed the start button filling two SxS cards with one take – a 114-minute shot. During that time 40 planes landed. The frame remained absolutely still, no registration movement, no dancing grain…I wasn’t sure this stillness would be acceptable, but then a plane passed through the frame providing momentary movement. Ten seconds later a wind vortex produced by the passing plane sang though the frame and disturbed one loose branch hanging from a nearby tree… When the next plane landed it started all over again…When I looked at the footage on my computer that night I realized I had recorded an action that would have been impossible to capture on film.”

In the film, this shot lasts roughly seventeen minutes, in which 4 of the 40 captured planes are seen landing. Just like in the coke tower scene, any jumps in time that Benning added in post-production are imperceptible. What we see in the film dictates that there are approximately 4 minutes between the landing of the first plane and the landing of the second; however, it is anyone’s guess as to how much time actually passed between the original landings of these two planes, or even if there were other planes that landed in between them. What we are aware of while watching this shot, though, is the potentiality that Benning recorded a large stretch of uninterrupted footage, and is presenting the viewer with his most ideal representation of this event.

This boundless, uninterrupted palette of moments likens the editing process to the more subjective, ‘hands-on’ artistic medium of painting. Rodowick quotes Thomas Elsaesser’s “Beyond Distance”, in which Elsaesser writes, “…the digital image should be regarded as an expressive, rather than reproductive medium, with both the software and the ‘effects’ it produces bearing the imprint and signature of the creator”. Rodowick adds, “The image becomes not only more painterly but also more imaginative.13” This is such a monumental quality for video to have, not only because it validates its place among more traditional fine art media, but because it gives it an edge against celluloid as a tool for artists’ and filmmakers’ creative and subjective freedom. When a shot is captured on celluloid, the potentiality of missed moments – via reel changes – comes into play. Therefore, because there are moments in the entire duration of the captured event that are ineligible for inclusion in the final presentation, the viewer cannot be confident that the filmmaker was allowed to curate the duration down to his most desired selection. This is akin to denying a painter access to certain viewing angles of his model, or the use of particular, appropriate brushes.

Michael Snow’s Solar Breath, thus, both suffers and reaps rewards from video capture’s potentialities. As a presentation of a long, continuous shot of wind playing and fighting with the window drapes, the indexicality of the duration of this event is dubious from the moment it is clear that it was captured in video. We see three or four instances in which the drapes blow forward to reveal the outdoors, but the intervals in which these, or any change, occur is shrouded in doubt and cannot be assumed to be an accurate representation of the real duration (this, of course, disregards situations in which an artist may explicitly state his faithfulness to the captured material in the editing process, which itself is a rare circumstance that cannot be read into the long-term interpretation or perception of the work).

On the other hand, Solar Breath’s capture method instills a subjectivity and creative freedom into the work via this same slight-of-hand potentiality. Like Benning’s hour-long coke tower shot, or his fifteen minutes of overhead planes and rustling twigs, Snow’s film is viewed with the possibility that the bit that we are seeing is only a fragment of the entire capture. Solar Breath isn’t randomly 62 minutes long; it is that length because Snow didn’t want it to be any longer or shorter. The piece presents the moments from the original shoot that Snow deemed to be worthwhile; the distance between the first and the second glimpses into the outdoors is what it is because Snow didn’t feel the need to shorten it (or even lengthen it). The potential for greater authorial control in the duration grants what is seen more weight as an expression of Snow’s tastes and intuitive sense of temporal composition. It is not just the work of nature, but a collaboration between Snow and nature.

Recalling Bazin’s ideas on the ontology of the photographed image, he likened it to a mummification of the model, and he saw film as the mummification of change in the model. Furthermore, these media were proof that the model and its changes existed, unaffected by the image’s distortions in focus, discoloration, or incorrect aspect ratios. As Bruce Elder explained in his dissection of Michael Snow’s film Presents,14 an image is not indexical when there is distortion, and this is detailed in the opening minutes of Presents when the squished image of a naked woman becomes completely unrecognizable as a representation of a human being. Likewise, then, any distortion of time in a moving image should be seen to diminish the image’s indexicality of the model’s change. This is the most liberating feature of video as a documentary medium. In the takeover of photography in the first few decades of the twentieth century, Bazin purported that “Photography is thus manifestly the most important event in the history of the visual arts. Both deliverance and fulfillment, it enabled Western painting to rid itself once and for all of its obsession with realism and to rediscover its aesthetic autonomy.”(“Ontology of the Photographic Image,” 10) Likewise, video’s inability to objectively present a durational event allows the medium to jump right into its own autonomy: the unquestionable faith that the image and its duration represent the artist’s uncensored intuitive vision.

Citations

- André Bazin, “The Evolution of Film Language,” What is Cinema? Caboose,

Montreal, QC, 2009: pg. 91.

- D. N. Rodowick, “The Incredible Shrinking Medium,” The Virtual Life of Film.

Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 2007: pg. 7.

- Clement Greenberg, “Modernism,” Clement Greenberg – The Collected Essays and

Criticism: Volume 4 – Modernism with a Vengeance (1957-1969), The University

of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL and London, UK, 1993: pg. 86.

- P. Adams Sitney, “Structural Film,” Film Culture, no. 47 (Summer, 1969), pg. 327.

- Annette Michelson, “Toward Snow: Part 1,” Artforum, 5:10 (June, 1967), pp. 175-76.

- Michael Snow, “A Statement on Wavelength for the Experimental Film Festival of

Knokke-le-Zoute,” Film Culture, no. 46, (Autumn, 1967), pg. 1.

- Pier Paolo Pasolini, “Observations on the Long Take,” October, Vol. 13 (Summer,

1980), pp. 4-6.

- André Bazin, “Ontology of the Photographic Image,” What is Cinema? Caboose,

Montreal, QC, 2009: pg. 3-10.

- D. N. Rodowick, “An Ethics of Time,” The Virtual Life of Film. Harvard University

Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 2007: pg. 85.

- Mark Peranson, “Ruhr,” Cinema Scope, Issue 41 (Winter, 2010), pg. 57.

- James Benning, Interview with Michael Guillen, “Darkest Americana & Elsewhere:

Ruhr: A Few Questions For James Benning,” Twitchfilm, March 2, 2010,

link.

- James Benning, “Knit & Purl,” Cinema Scope, Issue 40 (Fall, 2009), pg. 39.

- D. N. Rodowick, “Paradoxes of Perceptual Realism,” The Virtual Life of Film.

Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 2007: pg. 106.

- Bruce Elder, “On the Concepts of Presence and Absence in Michael Snow’s

Presents,” in Wees, William C. and Michael Dorland, eds. Words and Moving

Images. Mediatexte, Montreal, QC, 1984: pp. 34-51.