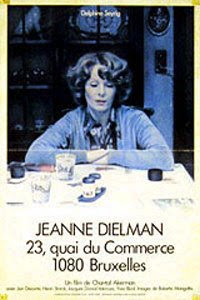

The structure of a French housemom’s life of chores structures Akerman’s monstrous structural film, the shortest two-hundred minute film I think I will ever see. Jeanne Dielman, a middle-aged, single mother, leads an improbably stereotypical life, the demolition of which is one of Feminism’s primary raisons d’être. The monotony and ritualism of it all is exhausting, but also mesmerizing and seductive. The ability to endure living such a life is heavily reliant on the flow state of consciousness, and Akerman’s masterful technique of luring her audience into the same flow state that Dielman is participating in is the main reason why the film flies by so easily; it’s cinematic hypnosis. Jeanne Dielman can dedicate twenty minutes to trying to make a decent cup of coffee, or knead her meatloaf to perfection, and I’m right there with her. I struggled between wanting to look at her face and wanting to keep my eyes on whichever chore she was currently doing, especially the meatloaf. It was the same experience as watching a scene in which a character receives a massage: total relaxation. There were a couple of moments where the camera would cut and relocate mid-chore, often to a less desirable angle on the action. This was slightly frustrating for me, having recently sat through 13 Lakes, because I theorize that the camera was moved when a reel ended. Akerman’s camera is never in motion in this film, and she will often sit it in place for the duration that Akerman is in a room, and switch to the next room she enters the moment she exits. When something takes too long, though, like the bravura coffee-making, the reel change is accompanied by an angle change, too. I assumed that this is to make the cut less distracting. This is minor, though, and my mild irritation can be attributed to the fact that Akerman was able to make so many instances of ultimate mundanity so riveting.

The structure of a French housemom’s life of chores structures Akerman’s monstrous structural film, the shortest two-hundred minute film I think I will ever see. Jeanne Dielman, a middle-aged, single mother, leads an improbably stereotypical life, the demolition of which is one of Feminism’s primary raisons d’être. The monotony and ritualism of it all is exhausting, but also mesmerizing and seductive. The ability to endure living such a life is heavily reliant on the flow state of consciousness, and Akerman’s masterful technique of luring her audience into the same flow state that Dielman is participating in is the main reason why the film flies by so easily; it’s cinematic hypnosis. Jeanne Dielman can dedicate twenty minutes to trying to make a decent cup of coffee, or knead her meatloaf to perfection, and I’m right there with her. I struggled between wanting to look at her face and wanting to keep my eyes on whichever chore she was currently doing, especially the meatloaf. It was the same experience as watching a scene in which a character receives a massage: total relaxation. There were a couple of moments where the camera would cut and relocate mid-chore, often to a less desirable angle on the action. This was slightly frustrating for me, having recently sat through 13 Lakes, because I theorize that the camera was moved when a reel ended. Akerman’s camera is never in motion in this film, and she will often sit it in place for the duration that Akerman is in a room, and switch to the next room she enters the moment she exits. When something takes too long, though, like the bravura coffee-making, the reel change is accompanied by an angle change, too. I assumed that this is to make the cut less distracting. This is minor, though, and my mild irritation can be attributed to the fact that Akerman was able to make so many instances of ultimate mundanity so riveting.

The ‘ending’ comes out of nowhere, and is a huge point for discussion, as it changes one’s interpretation of the film so drastically (not Sixth Sense drastic, fortunately, but still). The film certainly doesn’t need it; however, the closing shot of Jeanne at the dining table certainly benefitted, and her euphoric expression of exhaustion had me smirking until the credits finally show up. It made me think of Daniel Plainview’s already iconic ‘I’m finished’ line, as Dielman might have been waiting for years to finally do what she did. Is she so depleted, sitting at the table, because she has now completely gone off the deep end, or has she just relieved herself of a lifetime of pent up tension and frustration toward the conventional female lifestyle that she has effectively just destroyed for herself? The ominous, alien flicker that has penetrated her home for the duration of the film seems to finally hit her at this point; it’s a strange and incredibly intrusive luminance, but had become just another routine thing that is always there and accepted as such.

The film is lightly littered with sly references and commonalities to like-minded avant garde shorts from the 1970s, like Martha Rosler’s angry and cynical Semiotics of the Kitchen and Standish Lawder’s beautiful and pessimistic Necrology. The former damns the woman’s place in the kitchen, as a young lady shows off her knowledge of the tools of the kitchen, alphabetically, so to make the lesson more accessible to the next generation of girls. Rosler presumably hates women like Jeanne more than anything, someone who knows, rhythmically, the ins and outs of a kitchen. A brief shot of Jeanne drifting down an escalator while she is out running errands equates her life to one of the swarm of working class New Yorkers descending to their doom in Necrology. Jeanne is healthy, relatively young, has a luscious head of red hair, and is superficially happy; but, like the cast of Lawder’s film, she is dead already.