Though I still haven’t seen Gerry, I think it is safe to say that this is going to be my favorite film in Van Sant’s Death trilogy, and is also my favorite of any of his films. There are a few things that I rely on appreciating when I go into a 21st century Van Sant film: long tracking shots, minimalism, and out-of-nowhere homoeroticism. All of these get big check marks in Last Days. The film got a lot of hoopla for being related to/about/referencing Kurt Cobain and his death. I don’t care or know anything about Nirvana of Cobain’s life; I don’t think I can name three of their songs. So I went into this trying to ignore that aspect of it, despite having to acknowledge its Warhol-esque pop culture cynicism. Formally, the film seems perfectly designed to put off Cobain enthusiasts who rushed into the film for a biopic on their fallen hero, which is the most likely reason this film has such an outspoken and inapporpriately negative reputation. The film really isn’t changed at all by Cobain’s name or legacy; this is a film about a distraught musician on his last leg. Fame doesn’t come into play at all, though I’m sure many people who see that as being a factor in Cobain’s suicide force that into their readings of the film; the film doesn’t attempt to answer any questions about why the protagonist is so depressed, because it has better things on its mind.

Though I still haven’t seen Gerry, I think it is safe to say that this is going to be my favorite film in Van Sant’s Death trilogy, and is also my favorite of any of his films. There are a few things that I rely on appreciating when I go into a 21st century Van Sant film: long tracking shots, minimalism, and out-of-nowhere homoeroticism. All of these get big check marks in Last Days. The film got a lot of hoopla for being related to/about/referencing Kurt Cobain and his death. I don’t care or know anything about Nirvana of Cobain’s life; I don’t think I can name three of their songs. So I went into this trying to ignore that aspect of it, despite having to acknowledge its Warhol-esque pop culture cynicism. Formally, the film seems perfectly designed to put off Cobain enthusiasts who rushed into the film for a biopic on their fallen hero, which is the most likely reason this film has such an outspoken and inapporpriately negative reputation. The film really isn’t changed at all by Cobain’s name or legacy; this is a film about a distraught musician on his last leg. Fame doesn’t come into play at all, though I’m sure many people who see that as being a factor in Cobain’s suicide force that into their readings of the film; the film doesn’t attempt to answer any questions about why the protagonist is so depressed, because it has better things on its mind.

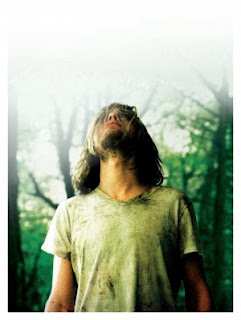

Despite standing on its own in a fictional universe, the film, like Elephant, gains a great deal of tension by the audience knowing that scenes of death are coming. Unlike in Elephant, Last Days leaves those expectations unsatisfied. The climax isn’t an intense killing spree or moment of reflection. When Blake (Michael Pitt) is found dead at the end, I was surprised at how unmomentous it is. It felt to me as if about five minutes of the film were missing that lead to the death. I wasn’t even sure that the body was Blake’s until his ghost crawls out of him and climbs up the windows panes, presumably into heaven. This scene is beautiful and strangely avant garde, flattening the space of the environment to allow for Blake’s ghost to grab areas of the frame that are out of reach in reality. Its a brilliant way to show the new reality that death would bring if there were an afterlife; time and space cease to exist in any comprehensible form. Thus, this gives the film a significant sense of spirituality that is either absent or only hinted at in the more realist Elephant. Not that Elephant is missing spirituality, it doesn’t call for anything of the sort. But it is a huge reason why I prefer Last Days. It’s a satisfying and baffling payoff to the meandering meditation that makes up the rest of the film, and is the most optimistic of any of Van Sant’s finales that I’ve seen.