When I was in the 4th grade, I lost the spelling bee because I mispelled the word ‘epic.’ I spelled it E-P-I-K. Pretty pathetic for a nine year-old. When I told my best friend, he slapped me. I knew the word because there were blockbuster films that were advertised as being epic on the TV spots, but I didn’t have any recollection of actually reading the word. In terms of filmmaking, I think that there are ‘Epic” films, and I think that there are ‘Epik’ films. ‘Epik’ films are defined by their budgets and mainstream appeal, B-movies that feature internationally recognized celebs playing dress-up in front of green screens, films that don’t earn their excessive running times. These films are films that I avoid, and when I am tricked into seeing one (most recently, The Dark Knight) it makes me crave all-the-more a seventy-five minute art film about a man in a row boat, or two people having a dinner conversation. But, then there are the ‘Epic’ films, that restore my faith in ambitious filmmaking. Fitzcarraldo is one such film. While I was watching the visual climax of this film, a memory of a making-of documentary of Titanic that I saw around late 1997 crossed my mind. The crew of that film made a pretty exact replica of the Titanic, about 1/50 of its original size, and filmed it in a large pool of water to get a lot of their effects shots. Despite all of the precision and tedium and craft that went into making that replica for those scenes, it doesn’t even come close to producing something as magical, grand, and real as what Werner Herzog pulls off in this movie.

When I was in the 4th grade, I lost the spelling bee because I mispelled the word ‘epic.’ I spelled it E-P-I-K. Pretty pathetic for a nine year-old. When I told my best friend, he slapped me. I knew the word because there were blockbuster films that were advertised as being epic on the TV spots, but I didn’t have any recollection of actually reading the word. In terms of filmmaking, I think that there are ‘Epic” films, and I think that there are ‘Epik’ films. ‘Epik’ films are defined by their budgets and mainstream appeal, B-movies that feature internationally recognized celebs playing dress-up in front of green screens, films that don’t earn their excessive running times. These films are films that I avoid, and when I am tricked into seeing one (most recently, The Dark Knight) it makes me crave all-the-more a seventy-five minute art film about a man in a row boat, or two people having a dinner conversation. But, then there are the ‘Epic’ films, that restore my faith in ambitious filmmaking. Fitzcarraldo is one such film. While I was watching the visual climax of this film, a memory of a making-of documentary of Titanic that I saw around late 1997 crossed my mind. The crew of that film made a pretty exact replica of the Titanic, about 1/50 of its original size, and filmed it in a large pool of water to get a lot of their effects shots. Despite all of the precision and tedium and craft that went into making that replica for those scenes, it doesn’t even come close to producing something as magical, grand, and real as what Werner Herzog pulls off in this movie.

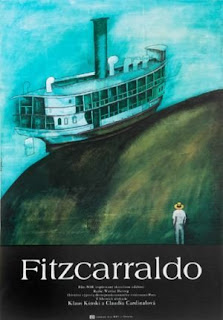

The premise of a man trying to build an opera in a village in the jungle is as out-there as one could expect from a Herzog film, and it utilizes one of his most prominent themes of a man who is passionate about something, and the peculiar detours that are encountered in his attempt to satisfy that passion. While Kinski plays the title character well, creating the kind of ferocious madman that was called for in this role, the real protagonist of the film is the opera genre. Fitzcarraldo’s love for the opera is what drives the film, and it is the main motivation for such stunts as dragging a massive ship over a mountain. Any arrogance or madness that is present in Fitzcarraldo’s character is born through the Carusos and Wagners of the world. These men’s works have possessed this man into a kind of operatic being that is probably not even capable of doing something in a manner that isn’t grandiose and dramatic.

As Herzog calls this film his ‘greatest documentary,’ it is worth bringing up Herzog’s similarities to the character Fitzcarraldo. Any ambition and madness that consumed Fitzcarraldo to drag the ship over the mountain is equally present in Herzog. Both are doing this huge task for the sake of bringing art to the masses, or perhaps the artless. I have no doubt that the arrogance of the title character is present in the filmmaker, too, but it is also outlined with modesty. Spoiler – – – The film ends with Fitzcarraldo failing somewhat in his venture to build an opera house in Iquito, but he still is able to scrap together a performance of Bellini’s I Puritani on the boat that he dragged over the mountain for the village to watch from the lakeshore. Fitzcarraldo, earlier shunned and scolded when he played Caruso over his record player, isn’t humble in his reception of the villagers’ awe, but I got the sense that he earned his moment of glory, as he managed, in his failure, to still pull off something new and epic for these people, even relative to the normal conditions of opera, just as Herzog did with this film.