This is definitely more accessible than Colossal Youth, with its shorter length and hints of a plot, while still feeling like it is part of the same universe. Pedro Costa certainly gives it his all in showing these individuals who are real, but still live in an ominous, cave-live community. Clotilde and her sisters, with the exception of Tina (pictured in the poster) all look like variations of Bob from Twin Peaks; very masculine and straggly. The door motif is very present here, like in Colossal Youth, where the viewer can learn everything he needs to know about a character or a location based on the style or quality of a door in the frame. The poor lurk around in grimy dwellings that are either doorless or are hinged with doors that have been cut into pieces. Many of the women earn money as maids, and when they walk through metallic elevator doors to visit the homes that they are to clean, and that are sealed with fully intact doors with peep holes and doorbells and knocking devices, the women couldn’t feel more out of place.

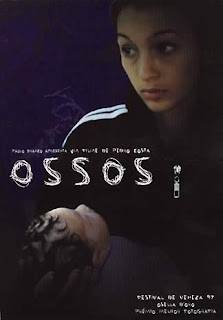

This is definitely more accessible than Colossal Youth, with its shorter length and hints of a plot, while still feeling like it is part of the same universe. Pedro Costa certainly gives it his all in showing these individuals who are real, but still live in an ominous, cave-live community. Clotilde and her sisters, with the exception of Tina (pictured in the poster) all look like variations of Bob from Twin Peaks; very masculine and straggly. The door motif is very present here, like in Colossal Youth, where the viewer can learn everything he needs to know about a character or a location based on the style or quality of a door in the frame. The poor lurk around in grimy dwellings that are either doorless or are hinged with doors that have been cut into pieces. Many of the women earn money as maids, and when they walk through metallic elevator doors to visit the homes that they are to clean, and that are sealed with fully intact doors with peep holes and doorbells and knocking devices, the women couldn’t feel more out of place.

The plot centers around a new born baby. It took me a while to figure out whose baby it is. I’m pretty sure that I know who the father is, as well as the mother, but I have doubts. The baby adds tension and plays a similar role as the baby in L’Enfant. There are pathetic attempts at feeding the baby, and nursing him, and selling him, and I always have the feeling that when he is not in the frame that he is lost rotting in a sewer somewhere. This film is plagued with just as much grief and hopelessness as Colossal Youth, but feels less monumental, granted it has much smaller goals. Ossos feels like a small movie in the vain of Battle in Heaven or Maria Full of Grace that shows the details of an unfortunate circumstance hounding a collection of unfortunate people. There is much less to digest here than Colossal Youth, but the roots of that film are clearly forming in this one.