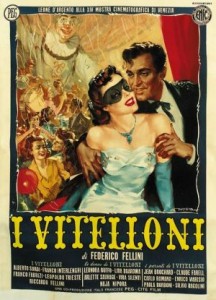

I Vitelloni (1953, Federico Fellini) – 3.5

Moved into the ‘re-visit’ pile for, let’s say, 10 years from now, because clearly I’m missing something at the moment that allows everyone else to connect with these characters. I tried to see if it was just a fluke mood I was in by watching some clips a couple of days later on youtube to see if they’d play any better for me, but no dice. It’s likely an aversion to Fellini’s tell-don’t-suggest style, which is evident, even at this early Neorealist stage in his career, from the opening montage introducing the characters. The narrator details, “Another day has come to an end. Nothing to do but go home, as usual” (italics mine), followed a couple of minute later by, “Just like every other night, only Moraldo walks the empty streets.” Perhaps this should be forgivable given that it’s just an opening, stage-setting bit of background info, but in this case, the ‘as usual’ and ‘just like every other night’ seem to be what the rest of the film actually details. For a film about the numbing mental and physical stasis of post-adolescent manhood, would it not be more poignant, compelling, engaging, etc. to actually learn of their lives’ monotony by experiencing it with them? As promised, these men have nothing to do to but lounge around, sleep with women who aren’t their wives, and partake in mildly amusing yet fleeting shenanigans, only to climax in a fairly beautiful escape for Moraldo, whose panning visions of his friends sleeping as he takes off for Rome effectively whisked me off into the relatively elating task of biking home. This is all more or less what happens in Diner (below), which is delightful; having watched Levinson’s film immediately after I Vitelloni just makes me suspect that Fellini’s portrait of bumbling hill-peakers is playing at a frequency that I am deaf to.

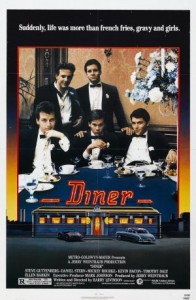

Diner (1982, Barry Levinson) – 6.9

I was surprised to learn that this was not my first Levinson experience (that would be Sphere, which I loved and lobbied for endlessly in middle school), and, more so, that this was nearly optioned into a TV series with Michael Madsen as Boogie (there was a 30-minute pilot, but it doesn’t look like it really got off the ground). Interesting, though, that the TV show was supposed to focus more on the wives, because the women in Levinson’s feature are the standout, with an extra special mention for Ellen Barkin, whose turn in the record cataloging fight would be enough to win me over for forever if her part in Shit Year hadn’t already done so. A film that will almost certainly shoot up with successive visits, it captured perfectly the crippling and often insanity-inducing incompatibilities that must be coped with for a relationship to work.

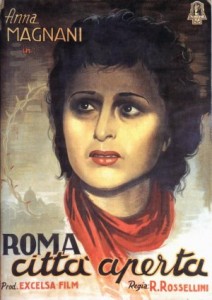

Rome, Open City (1945, Roberto Rossellini) – 7.6

Kind of the same idea, toward the end, as I Confess, but with grueling stakes that go beyond vanilla movie violence as the consequence. The first half sets up sympathetic characters with affectionate aspirations in life, and the brutal brevity with which these lives are obliterated is upsetting on a visceral level. A shocking act of violence removes a central character to the webbed narrative with whose life we’ve very much become complicit, closes the curtain on the first half, and does not relent as the second half ultimately verges on torture porn. The style is a well-seasoned balance of neorealism and Hollywood studio flair – the hopefulness of Hollywood crushed by the Italian tinges of wartime fatalism. Also, it ends up as a pretty damning portrayal of the consequences of catholic rituals, pretty much opposing Hitchcock’s heroizing of his faithful priest head-on.

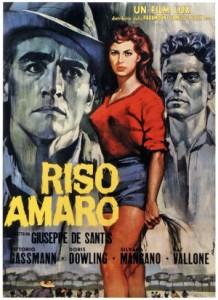

Bitter Rice (1949, Giuseppe De Santis) – 6.8

Captures a place, era, and struggle with supreme detail despite it’s classical flourishes (say what the programmers will, this film does not belong in an Italian Neorealism retrospective unless it is meant as an example of contemporary filmmaking going against the movement. Sure, it’s shot on location, but these are budding and seasoned actors in highly dramatic, noir-ish scenarios, lensed by intricately – not to mention elegantly – choreographed shots and set-ups. Even the pessimistic finale ended up feeling like a crowd-pleaser). The piles of rice become like sand dunes, locating the mythical-looking jewelled choker in a mise-en-scene fit for something more like some kind of ancient amulet. And it seems to have some sort of voodoo power anyway on these women, sending those who crave it (with ‘it’ being the choker, but also, basically, wealth & sex) into howling, writhing hysterics. Glides along toward its finale, which isn’t quite tragic, but nonetheless inevitable as if legend, with flair and nary a wasted moment. Had a strong sudden impact, but the airbags are deflating, and I presume this will not play well on another look (grumbles about an upcoming Criterion edition would facilitate that, however). Enthralling tracking shots of the possessed women were startling, terrifying, unsettling, but perhaps it was merely effective because, in the midst of a Neorealist retro, my expectations were for something far more subdued.