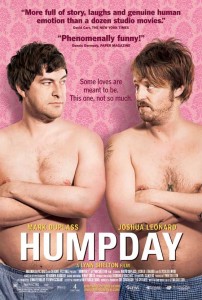

Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy, Kevin Smith’s Zack and Miri…, what I imagine to be mumblecore because I’ve never seen any of this mumblecore, and the Apatow-ish ‘what now?’ limbo between college and mid-life crisis: Humpday embraces its influences, and sputters while it sets up its contrived conceit before coasting on awkward, yet real, emotions. An old college friend shows up after a long hiatus to spend some time with his more stable, and married, bud (just like Reichardt’s set-up, basically). But where Old Joy focuses on the impossibility of undoing the ‘growing-apart’ that people inevitably face when they spend time away from each other, Shelton pushes that aside and says ‘let’s make them fuck”. After a rocky effort to set up this scenario (which I forgive because I usually suspend my disbelief for a film’s first third), the film becomes focused on some interesting facets of male sexual politics, stereotypes, and breaking down the idiotic institution that is marriage.

Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy, Kevin Smith’s Zack and Miri…, what I imagine to be mumblecore because I’ve never seen any of this mumblecore, and the Apatow-ish ‘what now?’ limbo between college and mid-life crisis: Humpday embraces its influences, and sputters while it sets up its contrived conceit before coasting on awkward, yet real, emotions. An old college friend shows up after a long hiatus to spend some time with his more stable, and married, bud (just like Reichardt’s set-up, basically). But where Old Joy focuses on the impossibility of undoing the ‘growing-apart’ that people inevitably face when they spend time away from each other, Shelton pushes that aside and says ‘let’s make them fuck”. After a rocky effort to set up this scenario (which I forgive because I usually suspend my disbelief for a film’s first third), the film becomes focused on some interesting facets of male sexual politics, stereotypes, and breaking down the idiotic institution that is marriage.

Ben, the married guy, is more open-minded than Andrew, the drifter, thinks he is; Andrew, inevitably, is more closed-minded than his hippie facade suggests. The subject of the film is the pending fornication that Ben and Andrew will partake in, but the meat of it is how this effects Ben’s relationship with his wife, Anna, with which he is currently trying, and struggling, to get pregnant. The strength of the film, from this point, is in the tension created by the social politics that the film is attempting to question: How should Anna feel that her straight man wants to sleep with another man? Does it matter that Andrew is obnoxious and flaky? Is the knowledge that Ben and Andrew were friends before Anna was in the picture a factor in the insecurities? If Ben and Anna were still in college, unmarried, would this dare be more acceptable to each of them? If so, why should marriage, a make-believe union that is used to mask insecurities of infidelity and the prevention of dying alone, change what they do, and how they interact, with other people? When Ben goes to that social gathering with Andrew, the night that the initial ‘deal’ was made, he sees a social setting that he hasn’t experienced in several years, a glimpse of what people his age are still capable of when free from invisible bonds of manners and ‘morality’. Sleeping with Andrew isn’t so much about confronting sexuality as it is about proving that his marriage wasn’t the end of living life the way he wants to.

Anna, the reserved, borderline-bitch wife, eventually becomes the not-so-sheltered wife with her own history of marital excursions: she got drunk and made out with someone in a bathroom. Ben’s reaction to this, obviously hurt and expressing the urge to guilt-trip her, is one of the film’s strongest moments, because it shows that he feels exactly the emotions that he is trying to get away from: the anti-experimental monogamy of a committed relationship. Humpday argues that this seemingly cultural taboo of polygamy is either so hardwired in us that we cannot break it without some serious self-reconstruction, or that it is, worse, innate. Though Anna theoretically cheated on Ben (at a time when he was, and intended to always be, faithful to her), it did not free her of anything. She had her fun, but came running back to the safety of her picket-fenced union with Ben, more happy than ever. The completion of this circle, then, relies on how Ben is affected by his own excursion (sleeping with Andrew). This is where allowing Ben and Andrew to not have sex, a resistance to portray how Ben reacts to marital deviancy, fails so massively. It closes off the male half of the debate, and makes the film’s entire argument incomplete (and, probably, pointless). At the same time, it shows the film’s homophobia, which twice interrupted a scene of homosexuality because of heterosexual reservations; the first instance belonging to Andrew, the second belonging to the filmmaker.