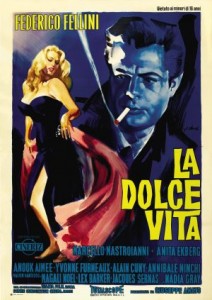

La Dolce Vita [1960, Federico Fellini] (7.5)

Fellini peaked early. None of the other nearly-dozen features I’ve seen have been quite as affecting. Assembling its episodes from tabloid headlines and rampant paparazzi culture from his youth, one gets the impression that he packed all of the best ingredients into one entrée, many of them (the flying Jesus and giant sea monster bookends, in particular) the most fantastical and colorful details of any of his films I’ve seen. Detailing the lifestyle of a man whose desire for glamour and hedonism conflicts with the impulse to settle down that is embedded in his (and his fiancée’s) DNA, it spells the conflicted hollowness and euphoria inherent in the life of the rich and famous, which ultimately leads them, as well as those who yearn for such a lifestyle, into insatiable unhappiness.

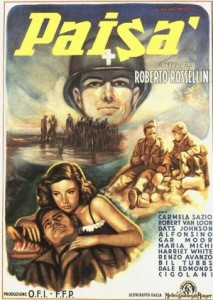

Paisan [1946, Roberto Rossellini] (5.7)

It was tempting to mark this as ‘Inc.’ because the print was so chopped up and many subtitles were missing, but in the end I think I got enough of it to know that it is just a set of shorts films in which some work much better than others. The portrayal of the Americans was unexpectedly multi-faceted, refusing to play them as excessively villainous or mindless (though the thick Southern accents didn’t help with that). Not sure if the fact that the Americans couldn’t remember what certain Italian characters looked like the day after spending isolated bonding time together was weak storytelling or a sly neurological racism worked into their character traits.

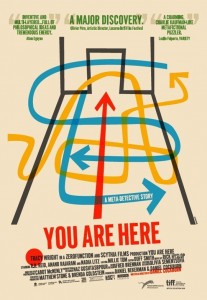

You Are Here [2010, Daniel Cockburn] (7.2; down from 7.7)

Handles many ideas that I’m currently grappling with, with enough DIY aesthetics, games and tests, and Wavelength references to leave me smirking the whole way through. The anecdotal structure is successful purely because the anecdotes are so provocative, and while they all deal with greater ideas of consciousness and self credited to John Searle, Cockburn positions them, returns to them so that it also becomes a dissection of the perceptive and cognitive components of movie-watching (most explicit in the film’s most chilling scene about an inventor who develops an computer eye for blind people, and then switched the programming so that everyone with the eye can only see what he sees). It is perhaps too precocious for its own good, not to mention that the compelling pedagogy of some of its sequences can cross a line into pedantically schooling the viewer, but it is undeniably inventive in its own resistance of conventional cinema logic or form, and holds itself together surprisingly well.

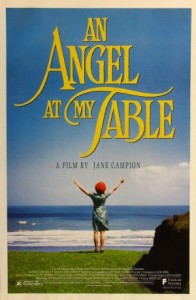

An Angel at My Table [1990, Jane Campion] (6.9)

I’m not quite sure why I respond so well to Campion’s deceptively conventional brand of (auto)biographical nostalgia, nor her episodic structures, which would normally leave me snoozing through their rambling, shapeless, sepia-toned running times (see: Terence Davies). There is an edge to her direction, with slightly off-timed line deliveries and lingering angles positioned at awkward heights, that makes it just, for lack of a better word, amateur enough to leave me hooked. She has a brand of quirk that isn’t manufactured, doesn’t care if it finds an audience, like she just needs an outlet and this is it. I thought this was Campion’s autobiopic until I learned it was Janet Frames (Janet as a pseudonym for Jane, poetry instead of filmmaking…not too crazy), which is as much in debt to the vibrancy and detail of Campion’s assemblage as it is to the similarity of her name to her subject’s.

Love Streams [1984, John Cassavetes] (6.4)

The one film by Cassavetes where the overwhelming positive is the filmmaking (i.e., photography, montage, lighting) rather than his usual excellence in script and direction. Viewed as the last ‘true’ film before he bastardized Big Trouble and then died an early death, it almost reads as a frankensteined greatest hits of scenes and characters from his earlier films: Sarah is clearly a resurrection of Mabel, while her relationship with Jack could be how Minnie and Seymour Moskowitz turned out after a decade or so of romance. Also, pretty sure Robert’s house was the same as the one used in Faces? Anyway, key characters are trying to convey love – a term that Cassavetes breaks his back over in an effort to abstract it further than it’s ever been – and have yet to negotiate for themselves the difference between tenderness and silliness, suggesting that while there really may not be a clearly-defined distinction between the two, it is downright toxic to display both forms simultaneously; in equal measure, they cancel each other out. The last reel of this film is a masterpiece, and a devastating final page in his oeuvre. It’s too bad that the rest of the film, while enthralling in spurts, suffers from some severe tonal imbalances, as well as some of the most self-consciously ‘heavy’ performances I’ve ever seen.

West Side Story [1961, Jerome Robbins & Robert Wise] (4.8)

Romeo and Juliet-ish take on mid-century race issues in NYC is about as gentrified as Giuliani’s Times Square. I hate that the Puerto Ricans are mostly white people in ‘brown face’, speaking in a faux-Latin accent that would get any white person’s ass justifiably kicked were it actually spoken in New York; I hate that after every musical number all of the characters pause, and then burst into cheers and high-fives to congratulate each other on the awesome choreography they just pulled off ‘spontaneously’ (I know this is kind of a signature of Broadway, but still); and I hate those god-awful songs that are not even the least bit catchy (except for maybe I Feel Pretty, and why God why do I have to have that song stuck in my head?). Loved the prolonged overture and opening with just ambient sound effects, and those sets sure are colorful. The one audacious stroke in the whole project was allowing the film to end without any of these hollow, irrational people getting to change. It ends when things are most dire and depressed, but, unlike the infinitely more incendiary Do the Right Thing (which does more or less the same thing), it feels entirely manipulative and unearned.