This being Kiarostami’s first feature film, it lacks much of the post-modernism from is Koker trilogy onward that makes his films multifaceted masterpieces of realism, but it still contains the prime characteristic that makes his films so remarkable, which is a giant heart. The film is founded on a mission to preach didactic morals on child behavior, not uncommon for a Kiarostami film (which almost certainly budded from his early educational shorts). This is not a negative trait, but is mildly detrimental only because it makes the plot somewhat predictable. The 1st act will be recognizable to anyone who has seen his Where is the Friend’s Home?, as both begin almost identically by focusing on two boys/friends at school, and follows one of them home from school where his mother badgers him about not doing his homework before he leaves to go out and play. Where Ahmed in Friend’s Home only wanted to leave to return his friend’s notebook, Qassem actually only wants to leave to go play soccer with his friends. He is the complete opposite in character from Ahmed except that they are both guided by their intuitive wills to go against the authorities’ wishes, to do what they want to do rather than what they should do.

This being Kiarostami’s first feature film, it lacks much of the post-modernism from is Koker trilogy onward that makes his films multifaceted masterpieces of realism, but it still contains the prime characteristic that makes his films so remarkable, which is a giant heart. The film is founded on a mission to preach didactic morals on child behavior, not uncommon for a Kiarostami film (which almost certainly budded from his early educational shorts). This is not a negative trait, but is mildly detrimental only because it makes the plot somewhat predictable. The 1st act will be recognizable to anyone who has seen his Where is the Friend’s Home?, as both begin almost identically by focusing on two boys/friends at school, and follows one of them home from school where his mother badgers him about not doing his homework before he leaves to go out and play. Where Ahmed in Friend’s Home only wanted to leave to return his friend’s notebook, Qassem actually only wants to leave to go play soccer with his friends. He is the complete opposite in character from Ahmed except that they are both guided by their intuitive wills to go against the authorities’ wishes, to do what they want to do rather than what they should do.

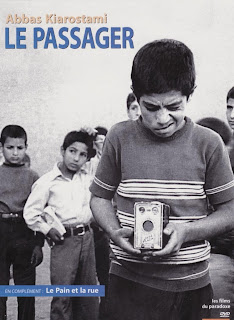

Qassem wants to attend a soccer match in Tehran where one of his idols will be playing in a big game. After mapping out the expenses of this two-day trip, and arranging the lies that he will tell his mother, he must find a way to raise (read: steal) enough money to afford the transportation fees. After he fails to barter an old, gutted camera to a pawn dealer, he ingeniously decides to pretend to use the broken camera to take people’s portraits for money, promising them printed photographs that they will obviously never receive. For more money, Qassem steals from his mother, and sells off his soccer team’s equipment. In every conceivable way, Qassem is the sort of kid that makes people hate children; that he still manages to earn my sympathy in the end is a testament to Kiarostami’s brilliance and skill at directing children.

I was surprised, and, frankly, impressed, that Kiarostami left Qassem in much pessimistic circumstances at the end of the film. Out of money, alone, hungry, and unsatisfied by the event that caused all of this mischief, Qassem may as well have been left for dead when the film fades to black. In leaving his protagonist, just a little boy, in such a wary and empty limbo, he really hammers home his morals and beliefs: You want to steal, cheat, slack off, and be an asshole to your friends? Get ready for a life of solitude and suffering. Kiarostami believes in the good and bad of his characters. Everything that could go wrong does go wrong for Qassem, but those characters who do deserve redemption are rewarded with some of the most blissfully happy endings that the cinema has to offer.