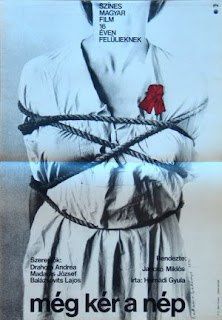

This was the only color film by Jancsó in Cinematheque’s series of four early films by the Hungarian filmmaker, as well as the only film shot in the academy ratio, rather than 2.35:1 widescreen, a more appropriate and less oppressive aspect ratio for his mise en scène. Perhaps I developed too much of an appreciation for his usage of the anamorphic scope, but he didn’t seem to adjust his compositional approach to the narrower frame, and therefore much of the action feels cropped here. Anyway, the film tracks a collective of Hungarian civilians who are participating in a protest or revolt, or perhaps they are reenacting a protest or revolt; it is difficult to decipher if this film is set in its 1890 setting or if it takes place in the present. There are some surreal moments early on, such as when a woman is shot in her hand, and the bloody wound miraculously becomes a red ribbon, or when a man is seemingly shot dead, but then stands right back up and continues his participation in the protest. These moments make the rest of the film fairly ambiguous in terms of its adherence to reality or its reliance on fantasy. Characters are shot (by guns), and it is unclear if they are really wounded or dead or not. The wounds, like bullet holes or cuts from knives, have obviously fake blood, and yet it is unclear if it is fake blood in the character’s universe, or just low-budget filmmaking. Some might praise this confusion of reality and fiction, but it is maddening in this film because it doesn’t make a difference either way. If it is a reenactment or if it is just a filmed account of the revolt, it’s still the same film. So why is it so irritating, then, if it doesn’t matter? Because this ‘revolt’ is a massive bore, and the viewer has no reason to care about any characters, nor the collective of people. If one doesn’t have an adequate knowledge of the Hungarian revolution from the mid-19th century, this film will do little to educate or give insight. The characters are also singing and dancing through much of the film. My sensitivity to musicals seems to be increasing, after my issues with Terrence Davies’ early films of family sing-alongs, and now with these anarchist folk songs that similarly mean nothing to me. 87 minutes rarely passes so slowly.

This was the only color film by Jancsó in Cinematheque’s series of four early films by the Hungarian filmmaker, as well as the only film shot in the academy ratio, rather than 2.35:1 widescreen, a more appropriate and less oppressive aspect ratio for his mise en scène. Perhaps I developed too much of an appreciation for his usage of the anamorphic scope, but he didn’t seem to adjust his compositional approach to the narrower frame, and therefore much of the action feels cropped here. Anyway, the film tracks a collective of Hungarian civilians who are participating in a protest or revolt, or perhaps they are reenacting a protest or revolt; it is difficult to decipher if this film is set in its 1890 setting or if it takes place in the present. There are some surreal moments early on, such as when a woman is shot in her hand, and the bloody wound miraculously becomes a red ribbon, or when a man is seemingly shot dead, but then stands right back up and continues his participation in the protest. These moments make the rest of the film fairly ambiguous in terms of its adherence to reality or its reliance on fantasy. Characters are shot (by guns), and it is unclear if they are really wounded or dead or not. The wounds, like bullet holes or cuts from knives, have obviously fake blood, and yet it is unclear if it is fake blood in the character’s universe, or just low-budget filmmaking. Some might praise this confusion of reality and fiction, but it is maddening in this film because it doesn’t make a difference either way. If it is a reenactment or if it is just a filmed account of the revolt, it’s still the same film. So why is it so irritating, then, if it doesn’t matter? Because this ‘revolt’ is a massive bore, and the viewer has no reason to care about any characters, nor the collective of people. If one doesn’t have an adequate knowledge of the Hungarian revolution from the mid-19th century, this film will do little to educate or give insight. The characters are also singing and dancing through much of the film. My sensitivity to musicals seems to be increasing, after my issues with Terrence Davies’ early films of family sing-alongs, and now with these anarchist folk songs that similarly mean nothing to me. 87 minutes rarely passes so slowly.