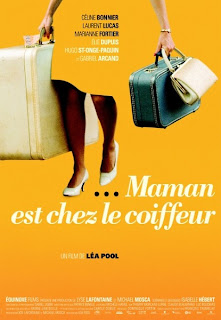

I had the chance to see this at the Toronto Film Festival, but ended up passing on it because it fit awkwardly into my schedule. The synopsis grabbed my attention, and then it started getting some pretty good reviews, so I regretted missing it. Fortunately, it was picked as one of Canada’s Top Ten, which are playing right now at the Cinematheque Ontario, and I was able to see it there. It took me until the second act to get into the rhythm of the film, but once it laid back on the cliches and the mother (played weakly by Céline Bonnier) left the picture, I was more interested in what was going on, and it even ended up being pretty moving throughout its final act.

I had the chance to see this at the Toronto Film Festival, but ended up passing on it because it fit awkwardly into my schedule. The synopsis grabbed my attention, and then it started getting some pretty good reviews, so I regretted missing it. Fortunately, it was picked as one of Canada’s Top Ten, which are playing right now at the Cinematheque Ontario, and I was able to see it there. It took me until the second act to get into the rhythm of the film, but once it laid back on the cliches and the mother (played weakly by Céline Bonnier) left the picture, I was more interested in what was going on, and it even ended up being pretty moving throughout its final act.

Mommy is composed of bright colors and infused with a general hokeyness that is reminiscent of an early Coca Cola commercial, and reminded me quite a bit of Haynes’ Far From Heaven (the look and the subject matter). The superficial perfection and underlying sense of something being wrong seems influenced by Blue Velvet, especially after a bird goes kamikaze on the kitchen window, and when some neighborhood teens gather in a closet to spy on one of their mothers undressing. The film feels like it could go in a couple of uninteresting directions in its first half hour (like focusing on the closeted father or the creepy deaf man) but deviated from them so much that I think that they were just MacGuffins. The real meat of the film is in the mother’s absence, and how that affects the family. Feminists will be pleased to know that the family pretty much disintegrates. The disintegration is handled well, and subtly enough. The star of the film is easily Marianne Fortier as 15 year old Élise, a Bressonian character that seems to absorb the downfall of the family singlehandedly. This film made me long for childhood more than Davies’ The Long Day Closes, even if it isn’t as obviously made by an auteur.

I was impressed by how unpretentious this film ended up being, which is probably why I was able to forgive it of its mistakes. There isn’t really anything flashy going on with the camera, editing, or music, so I was able to take it in more based on the story and the acting than the film as a piece of art. The film closes on a scene that should have been cheesy (it was a little, and had a few people in my audience burst into laughter) but felt honest. Élise races through a field with her youngest brother while the song ‘The Great Escape’ by Elie Dupuis plays over everything, creating an excessively sentimental finale that works. The cut to black after the hopeless idea suggested by Élise was a perfect and moving ending.