La Vie de Jésus (1997)

The title of Dumont’s debut suggests an examination of spirituality that I didn’t get from the film, suggesting either irony, pretension, or that I am immune to spirituality in films (could be the case, ie. my lack of appreciation for Davies and Bresson’s work). I liked this film, despite not agreeing with the title. The film focuses on a group of racist doofuses (doofi?), including the protagonist Freddy, and Freddy’s girlfriend Marie, who is being pursued by an Arab boy in town. The way that the plot unfolds is pretty predictable, but Dumont’s lulling style kept it interesting for me, and the abruptly graphic sex scenes do provoke… something. Freddy and Marie have aggressive sex inside and outdoors, seemingly moving it out into the wild to better frame the somewhat animal portrayal of their fornication.

The sex in this film is so unarousing that it magnifies the fraudulence of many art films that claim to have sex scenes that are unarousing, scenes that are there for the progression of the ideas in the film or for ‘art’s sake’ (Breillat came to mind). Dumont lenses the sex scenes as if he were filming cow sex. His characters seem to approach their sex in the same manner that I contemplate checking the mail: I kind of look forward to it, I do it every day, it only takes a few seconds, and I ultimately get no satisfaction out of it. Dumont sheds these characters of the minimal physical attraction they have in these scenes with unflattering close-ups and angles of parts of the body that even fit people usually try to conceal. The effect of these scenes is that I interpret the characters actions on a more innate and animal level. Murders and rapes come off as products of human nature, a sense to protect ones territory and invade the territory of others, rather than simply disturbed morals. The characters in this film are ugly people, and they make me feel a little bit more hopeless for mankind.

L’Humanité (1999)

Picking up where Jésus left off, L’Humanité could very well be focusing on the cop perspective of the previous film. Pharaon opens the film running through the hills of rural France, disturbed by something. He is soon revealed to be a member of the police, and then I was abruptly thrust into an investigation of the rape and murder of a young girl via a shot of her rotting vagina crawling with ants. The body seems to be in the same grassy field, covered maybe with the same ants that were crawling on Freddy, in the closing moments of Jésus. Though I was watching the ‘good guy’ perspective of a crime this time, the film has the same grimy mundanity of Dumont’s debut, and Pharaon’s neighbor and friends Joseph and Domino have the same sort of semi-abusive, territorial relationship that Freddy had with Marie. This film is doing more interesting things formally than Jésus was, though, and its pessimistic study of a man’s perception of humanity feels somehow epic.

The film is doing a lot of confusing things with the crime investigation genre that seems arbitrary to Dumont’s greater goals (much like his exploration of the horror genre in the consequent Twentynine Palms), but it did have me more engaged in the events than I was with Jésus. The meat of the investigation isn’t even introduced until well into the film, perhaps close to an hour into it, and the entire case disappears for long stretches of time and circles itself as if it wasn’t written by the same writer. Interviews are held with people for the sake of interviews, and the entire city seems to be sleepwalking in the aftermath of the tragedy.

Pharaon is the most complex, bizarre, and wonderfully conceived character in any of Dumont’s films so far. He has a naive holiness that makes me understand the Bresson comparisons a bit more than I did after Jésus, and it makes his relationships with anyone, especially Domino, have a tension and an emotion that is lacking in the other three films by Dumont. When Domino leaves Pharaon after they arrange to have dinner for the first time, Pharaon’s giddiness and physical elation is comparable to Adam Sandler’s dancing through the aisles of the dollar store in Punch-Drunk Love. He is awkward and pathetic and sad and genuinely cares for the good in people.

Spoilers — Dumont, showing that he can end his films with the best of them, closes the film with a kind of Silent Light-ish kiss of redemption. Pharaon had always threatened to inappropriately land a wet one on an unsuspecting person, and it goes over the edge at the end here with a shocking and blunt kiss where he seems to be trying to suck the sins out of Joseph. When the film closes with Pharaon in hand cuffs, I felt slightly cheated that Dumont ended the film with a silly and unnecessary ‘open-to-your-interpretation’ cliff hanger. However, after thinking about it a bit more, I think it’s okay, and I came up with a few versions of the ending that I’m not annoyed with.

Twentynine Palms (2003)

While I felt less enjoyment watching this than I did while watching La Vie de Jésus and L’Humanité, my thoughts at the end of it were leaning toward this being Dumont’s tightest film. For most of the running time, I had narrowed the film’s accomplishments to being a very elaborate and well shot Hummer commercial. What begins as a Hummer commercial, though, switches gears in the final twenty minutes, and becomes inarguably favorable to the Ford F-350 crew cab. The automobile metaphor is almost as explicit as the nudity and sex scenes, and half-way through I kept thinking to myself ‘okay, I get it.’ Katia, a French bimbo tagging along with her boyfriend David on some sort of getaway to Twentynine Palms, cannot drive. I guess her inability to operate the oversized vehicle is a way of showing her God-given incapability of handling an SUV (as offensive a metaphor as the actual Hummer commercial that suggests that men who eat tofu and eat healthily should buy a Hummer so that they can feel like men again). When she attempts to drive, she steers the slow-moving gas guzzler into bushes and cacti, scratching the paint job and upsetting David. Katia, pretty but a complete airhead, can’t do much of anything, actually, other than provide a hole for David. It was difficult for me to feel sympathy for her, even when the relationship gets abusive toward the end. David is even less likable than Katia, showing insufficient patience for Katia’s weakness in English and throwing temper tantrums that become more and more over-the-top and ridiculous toward the end of the film; the lack of a sympathetic character was the downfall for much of the film for me. However, I felt that the explosion of violence and plot at the end made sitting through the rest of it worthwhile, similar to how the end of The Brown Bunny redeems the tedium of the rest of the film (that film actually has several things very much in common with Twentynine Palms, including as the desert setting, endless driving, and explicit sex).

In Dumont’s films, women are the more dynamic characters, while the male characters all seem to be the same abusive, conservative honkies (save for L’Humanité‘s Pharaon). David is somewhat of a break from this type, in the sense that he seems (for some of the running time) to have a respect for a woman’s ability to think. He also is in a higher class than Dumont’s other male characters, has a decent job, and can at least afford a Hummer and an occasional vacation. That he evolves so abruptly into such a heartless beast is what made the end of the film so unsettling. While Dumont’s other males were somehow believable as rapists and murderers, David’s transformation is the only one that I can say I didn’t expect. There is a useless epilogue that makes up the final scene of this film and doesn’t work at all, ruining the disturbing images of the previous scene. I don’t know what Dumont was thinking when he scripted this, but it began as irritating and eventually came off as an attempt at comic relief. Other than that epilogue that I’m still trying to eliminate from my memory of the film, this is the film that has stuck with me the most out of all of Dumont’s work so far.

Flandres (2006)

I had the chance to see this in Cannes but passed on it after a guy in my line to see a different film that I can’t remember the names of said he saw it and thought it was nothing special and overhyped. I also hadn’t heard of Dumont before, so I passed, and it won the Grand Prix and I was kicking myself. That year, the judges were anti-war happy and fell for Wind That Shakes The Barley and gave it their top prize; it the blandest film I saw at the festival that year. I assumed that this was another film that was awarded for being European and ‘exposing the horrors of war’ and didn’t mind missing it too much. This is certainly a better war-themed film than Ken Loach’s bore, and is one of my favorite war films of all-time now (not that that’s a great accomplishment as I only like a few). It is modest enough to not approach The Thin Red Line‘s brilliance, but it is perfectly tight and effectively horrible. The film’s protagonist is Demester, but the star of the film is Adélaïde Leroux as Barbe. She is a beautiful and complex representation of what I imagine to be the ideal Dumont woman. More than any other slutty female in his oeuvre, every bad decision she made made me cringe and want to grab her and shake her for not being the nice, put-together girl that she should be. She is the main vertex of the love triangle between herself, Demester and Blondel. Demester is the kind of pathetic slob that defines most of the males in Dumont’s films, while Blondel, initially, appears to be the sort of ideal guy that a girl like Barbe should be interested in. The tension that is left in suspension when Demester and Blondel go off to war had me unusually engaged in both characters safety in the dangerous battleground that they unsuccessfully raid. The drama that was put on hold in Flandres from the love triangle would have made an interesting enough film, and so I found myself engaged in Demester and Blondel’s safety primarily for the sake of the excellent payoff once they both returned from the war, or, the more likely scenario, what would happen if one returned without the other. This film studies the complexity of pure masculine nature as seen by Dumont and juxtaposes it with the nature of war, and, as is shown in the ugly rape during battle, the treatment of man by man can be a disgusting thing. Dumont’s characters wander in a world approaching soullessness, and his combination of sex and combat in this film is a vile but potent representation of his core ideas.

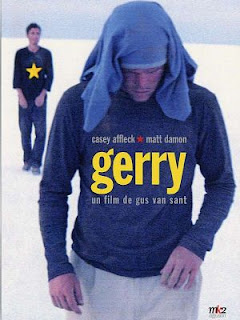

Certainly my least favorite of the Death trilogy, I think that viewing the trilogy out of order diminished the potency of Gerry for me. Had I seen Gerry when it was first released in the cinema as a follow up to Finding Forrester, I think that the sparseness and ambition of it would have been more jarring. I mean, it’s unsettling enough seeing a film with Matt Damon and Casey Affleck; who knew Damon would be willing to make a film with the other Affleck? As each film in the trilogy is based on a story that Van Sant read in the newspaper (two hikers getting lost in the desert, school shootings, Cobain’s death) I think that the shuffled Bostonian pairing must be at least somewhat significant to Van Sant’s pop culture obsessions. Van Sant credits Bela Tarr in the closing credits, who seems to be one of the main influences for this new style that Van Sant pulled out of the air. Though I think that the borrowed tracking shots and tone are welcome and fitting for these films, Gerry ever reaches the realistic mysticism of Tarr’s work (which I think he does reach in Elephant and Last Days). While moments of this film are hypnotic and beautiful, the meandering becomes, not boring like so many people complain, but tired. Some reviews I’ve read suggest this ‘would make a great short’ but I think that much of the endless wandering is essential. Perhaps shortening it to, a still feature length, 55 or 60 minutes would fit it well. I normally frown on suggestions for abbreviating films where ‘nothing happens,’ but I don’t get anything about of the 55min.-85min. segment of the film that I didn’t get in the first 45 minutes.

Certainly my least favorite of the Death trilogy, I think that viewing the trilogy out of order diminished the potency of Gerry for me. Had I seen Gerry when it was first released in the cinema as a follow up to Finding Forrester, I think that the sparseness and ambition of it would have been more jarring. I mean, it’s unsettling enough seeing a film with Matt Damon and Casey Affleck; who knew Damon would be willing to make a film with the other Affleck? As each film in the trilogy is based on a story that Van Sant read in the newspaper (two hikers getting lost in the desert, school shootings, Cobain’s death) I think that the shuffled Bostonian pairing must be at least somewhat significant to Van Sant’s pop culture obsessions. Van Sant credits Bela Tarr in the closing credits, who seems to be one of the main influences for this new style that Van Sant pulled out of the air. Though I think that the borrowed tracking shots and tone are welcome and fitting for these films, Gerry ever reaches the realistic mysticism of Tarr’s work (which I think he does reach in Elephant and Last Days). While moments of this film are hypnotic and beautiful, the meandering becomes, not boring like so many people complain, but tired. Some reviews I’ve read suggest this ‘would make a great short’ but I think that much of the endless wandering is essential. Perhaps shortening it to, a still feature length, 55 or 60 minutes would fit it well. I normally frown on suggestions for abbreviating films where ‘nothing happens,’ but I don’t get anything about of the 55min.-85min. segment of the film that I didn’t get in the first 45 minutes.